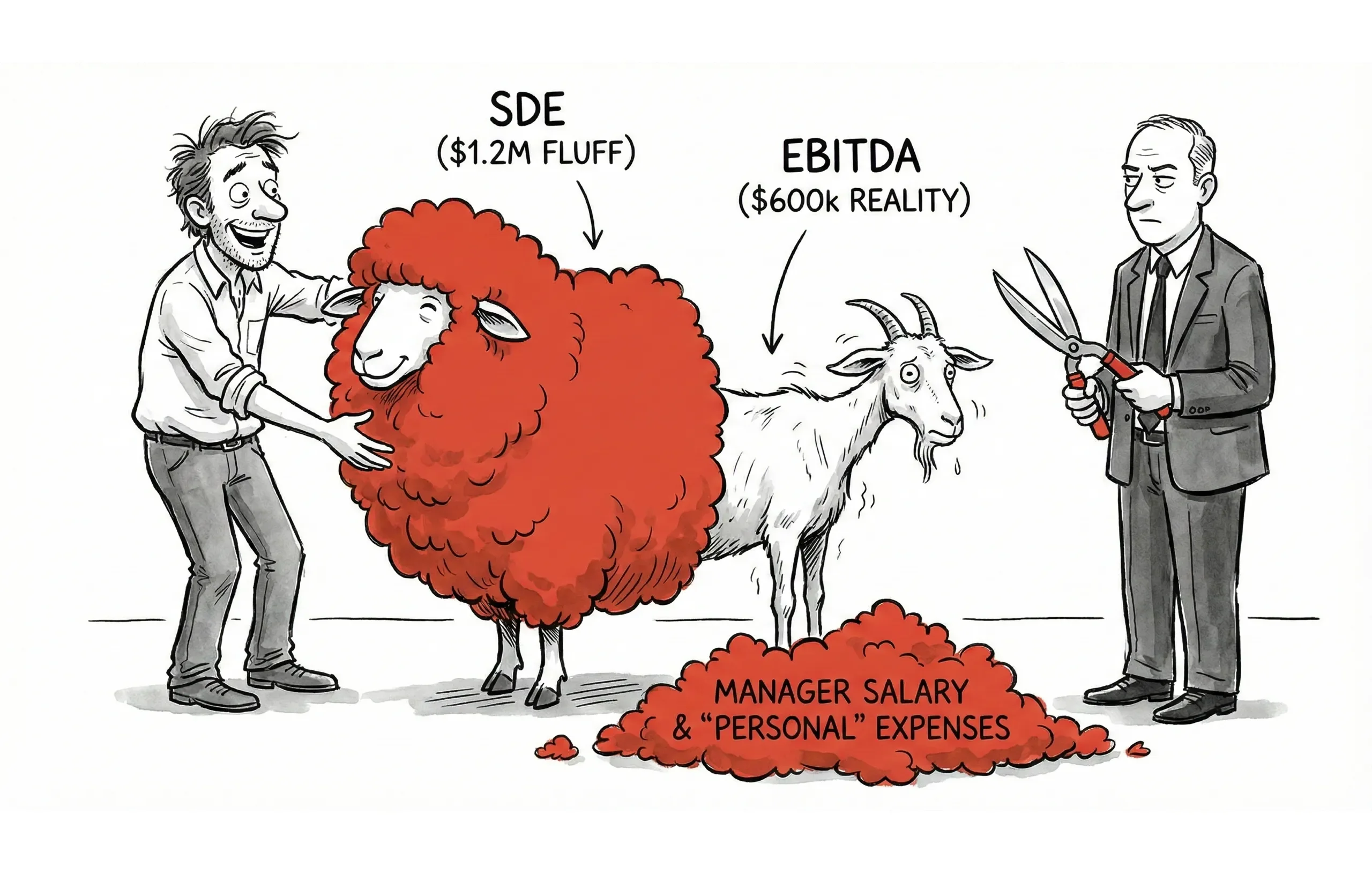

It’s the broker’s nightmare: You have a manufacturing client doing $5M in revenue. You’ve prepped the CIM (Confidential Information Memorandum) based on a healthy $1.2M SDE. You take it to a lower-middle-market private equity group, expecting a quick LOI.

Instead, they kick the tires and ghost you. Why?

Because while you were selling $1.2M in "Seller’s Discretionary Earnings," they were buying $600k in EBITDA. After they backed out the owner’s salary and hired a General Manager to run the shop, half the "profit" evaporated. To them, your 4x multiple looked like an 8x. The valuation gap wasn’t just wide; it was a canyon.

According to recent industry data, valuation gaps are the #1 reason small business deals fail to close (CPA Practice Advisor). Knowing when to switch from SDE to EBITDA isn't just an accounting exercise—it's how you keep deals alive.

The Core Difference between SDE and EBITDA

At its simplest: SDE is for buying a job; EBITDA is for buying an investment.

SDE (Seller's Discretionary Earnings)

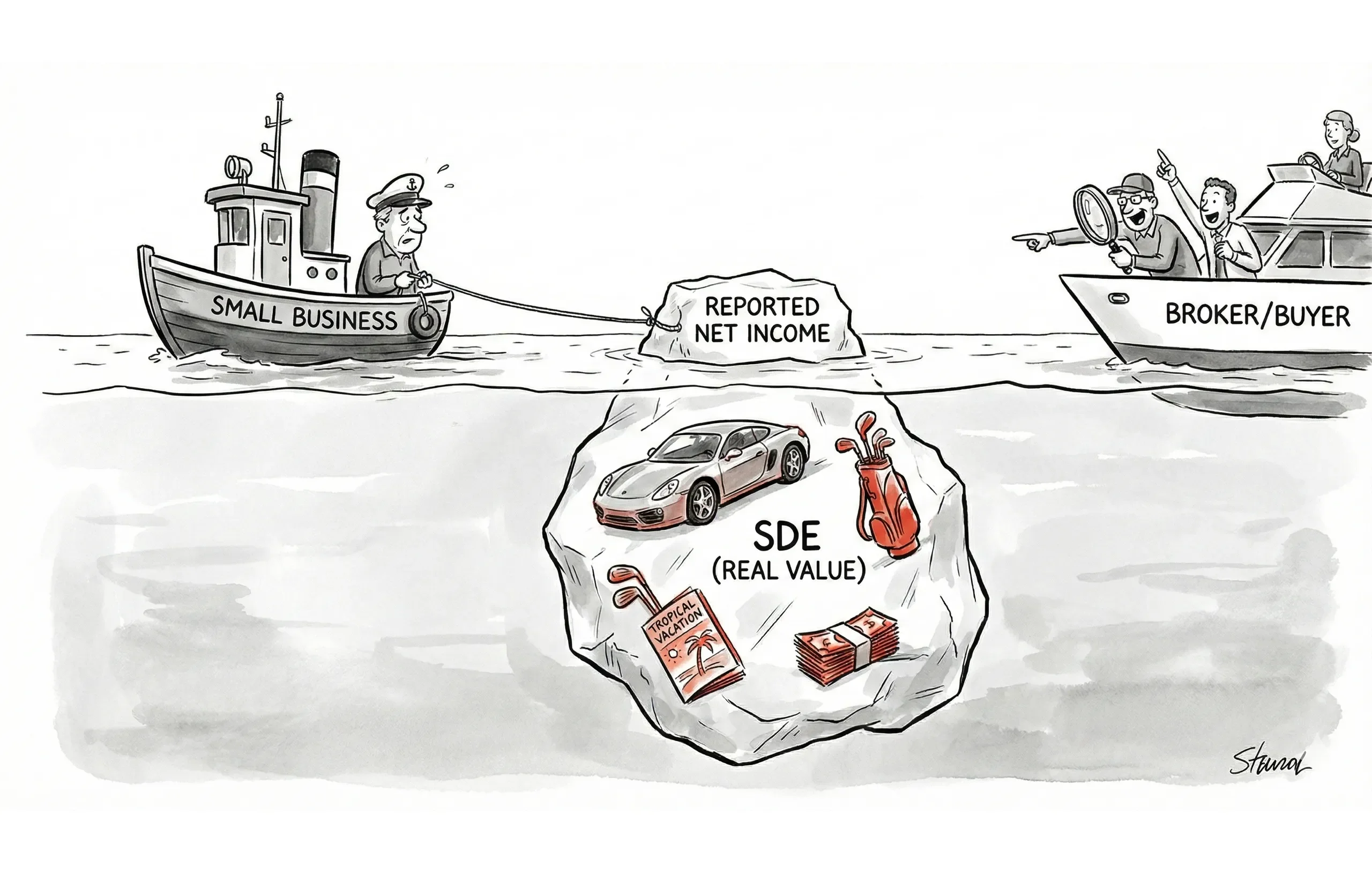

SDE is the total financial benefit available to a single active owner-operator. It answers the question: "If I buy this business and work 40 hours a week in it, how much cash ends up in my pocket?"

The Breakdown of Add-Backs

To arrive at the correct SDE, you take the Net Income reported on the tax return or P&L and add the following:

- Owner’s Salary & Benefits: This includes the owner's W-2 wages, payroll taxes, health insurance, and retirement contributions.

- Why? A new owner needs to know the total cash flow available to pay themselves.

- Owner’s Personal Expenses: Any expenses run through the business for tax benefits that are personal in nature (e.g., personal vehicle, family travel, cell phone plans).

- Why? These are not required to operate the business.

- Depreciation & Amortization: These are non-cash expenses used to lower tax liability.

- Why? These do not represent actual cash leaving the bank account.

- Interest Expenses: Interest paid on business loans or lines of credit.

- Why? The new owner will have their own debt structure (or buy cash), so the current owner's financing costs are irrelevant to the business's inherent value.

- One-time / Non-recurring Expenses: Unusual costs that are unlikely to happen again (e.g., a lawsuit settlement, a major website overhaul, or natural disaster repairs).

- Why? These distort the true historical earning power of the business.

Who uses it: Main Street buyers, SBA lenders, and individuals escaping the corporate grind.

EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, Amortization)

EBITDA measures the operating profitability of the business independent of the owner. It answers the question: "If I buy this business and hire someone else to run it, how much cash does the business generate?"

The Breakdown of EBITDA Components

To calculate EBITDA starting from Net Income, you "add back" the following:

- Interest: Financing costs are removed to focus on the profitability of operations regardless of how the business is funded (debt vs. equity).

- Taxes: Tax rates can vary by jurisdiction and strategy, so removing them allows for a clearer comparison of operating performance.

- Depreciation & Amortization: These are non-cash accounting entries. Adding them back shows the cash flow generation before capital expenditures.

Who uses it: Private Equity (PE) groups, strategic acquirers, and Search Funds.

The Cheat Sheet: Side-by-Side Comparison

If you are dealing with "tire kickers" who are confused about the numbers, show them this table.

Factor | SDE | EBITDA |

|---|---|---|

Owner Salary | Added Back (It's profit for the buyer) | Expensed (It's a cost to replace the owner) |

Assumes | Owner is the operator (CEO/GM) | Management team is in place |

Typical Deal Size | Under $2M - $3M | Over $2M - $5M |

Buyer Type | Individual / Owner-Operator | Financial (PE) / Strategic |

Typical Multiple | 2.0x – 4.0x | 3.0x – 6.0x+ |

SBA Financing | Primary metric used | Used for larger 7(a) deals |

When to Use SDE (The "Main Street" Standard)

You should use SDE for the vast majority of Main Street transactions. If the business relies on the owner to unlock the doors in the morning, it's an SDE deal.

Use SDE when:

- Revenue is under $2M (or earnings <$500k).

- The buyer intends to replace the seller as the operator.

- SBA financing is the primary funding vehicle.

- There is no second-tier management team.

Real-World Stats: According to the BizBuySell Insight Report, the average earnings multiple for "Main Street" businesses in 2024 hovered around 2.53x, with restaurants typically trading lower (2.0x-2.5x) and service businesses trading higher (BizBuySell).

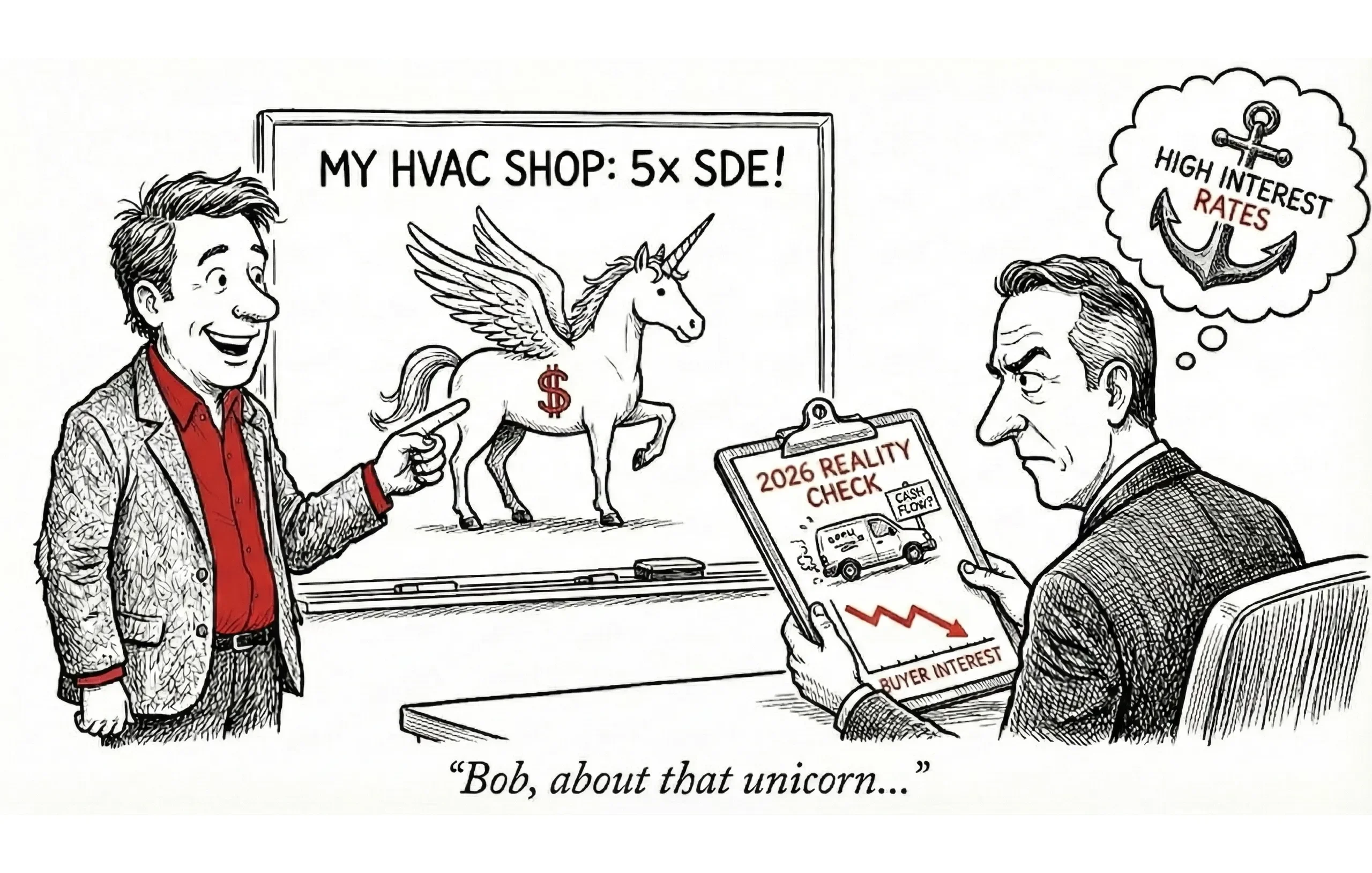

When to Use EBITDA (The "Institutional" Standard)

Once a business scales, buyers aren't looking for a salary; they are looking for yield. They have "dry powder" to deploy and need assets that run themselves.

Use EBITDA when:

- Business value exceeds $3M-$5M.

- A management team runs daily operations (the owner is strategic/passive).

- You are targeting Financial Buyers (Private Equity) or Strategic Competitors.

- The business has systems that function without the owner’s presence.

Real-World Stats: The Raincatcher and GF Data reports indicate that Lower Middle Market EBITDA multiples (deals <$25M) typically range from 4.0x to 6.0x, jumping significantly for "platform" quality deals in healthcare or software (Raincatcher).

The Pivot: Converting SDE to EBITDA

This is where deals often die. You need to normalize the earnings to speak the buyer's language.

From SDE to EBITDA (The "Management Haircut")To convert SDE to EBITDA, you must subtract the cost of replacing the owner.

SDE

- Market-Rate Replacement Salary (e.g., GM salary)

- Payroll Taxes & Benefits on that Salary= Adjusted EBITDA

Why it matters:Let's say you have an HVAC business with $600k SDE.

- SDE Buyer: Sees $600k. Pays 3x. Price: $1.8M.

- EBITDA Buyer: Sees that it costs $150k to hire a GM. Adjusted EBITDA is $450k. They pay 4x. Price: $1.8M.

Note: The math often converges at the same valuation, but the optics change. Presenting $600k EBITDA to a PE firm when it's actually SDE makes you look amateur.

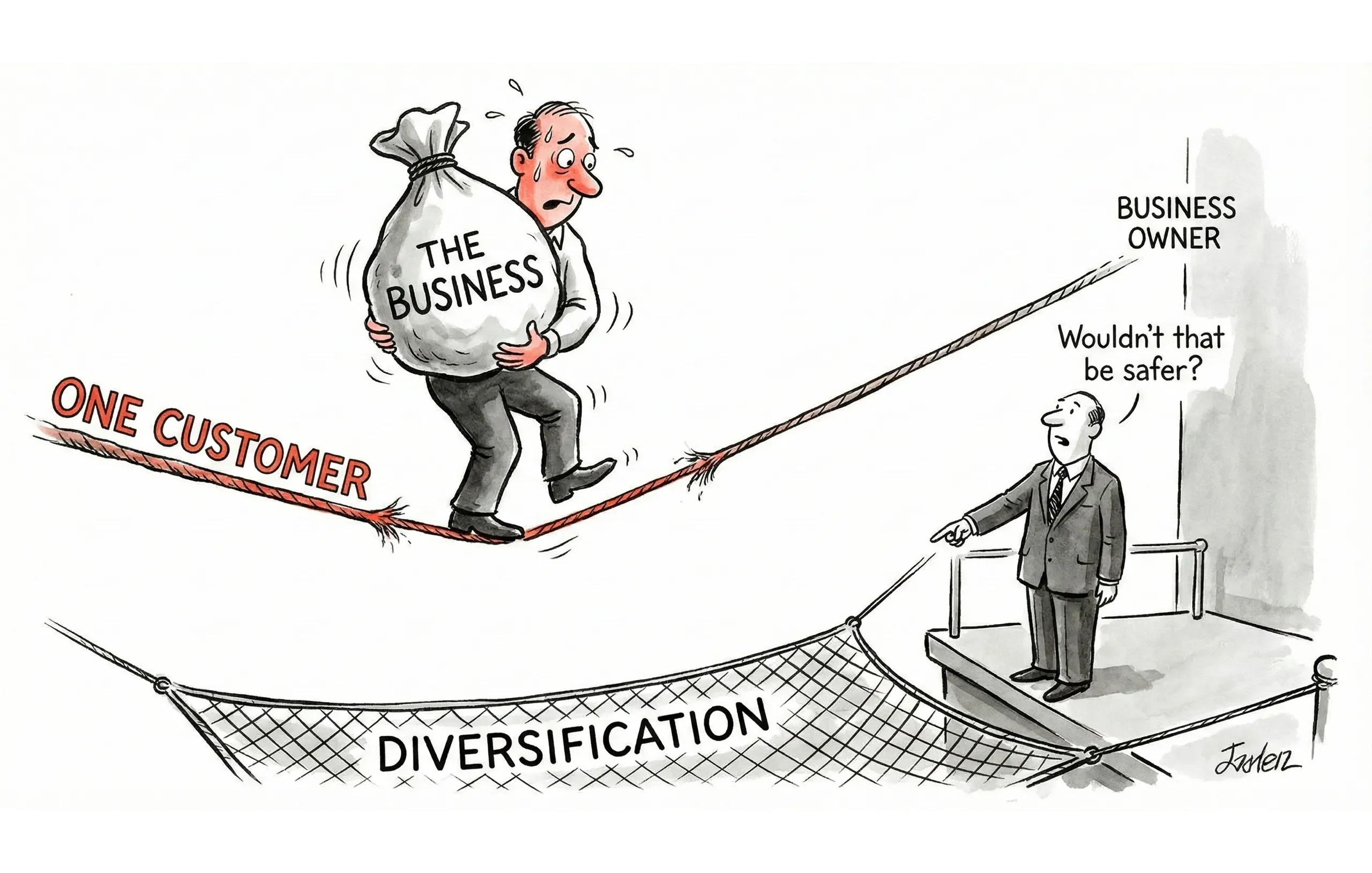

The Gray Area: The $2M - $5M "No Man's Land"

This is the hardest zone for brokers. The business is too big for most individuals (requires too much cash down) but too small or "owner-heavy" for many PE firms.

Strategy for the Gray Zone:

- Calculate Both: Have both an SDE and Adjusted EBITDA figure ready in your file.

- Qualify the Buyer Early: Ask, "Are you planning to run this yourself, or put a manager in place?"

- If they run it -> Quote SDE.

- If they manage it -> Quote EBITDA.

- Check the Bench: If the business has a strong #2 (like an Operations Manager), lean toward EBITDA. If the owner is the manager, lean toward SDE.

Current Market Multiples (2025 Benchmarks)

Keep these ranges in mind when setting expectations.

SDE Multiples (Main Street)

SDE Range | Typical Multiple |

|---|---|

$100k - $200k | 1.8x - 2.5x |

$200k - $400k | 2.0x - 3.0x |

$400k - $750k | 2.5x - 3.5x |

$750k - $1M+ | 3.0x - 4.0x |

EBITDA Multiples (Lower Middle Market)

EBITDA Range | Typical Multiple |

|---|---|

$500k - $1M | 3.0x - 4.5x |

$1M - $2M | 4.0x - 5.5x |

$2M - $5M | 4.5x - 6.5x |

$5M+ | 5.0x - 8.0x+ |

(Sources: BizBuySell, GF Data via Mercer Capital)

Common Deal Killers

1. The "Double Dip"

Mistake: You add back the owner's salary to get SDE, but then apply a high EBITDA multiple (e.g., 6x) to that number.Result: You overprice the business by 50%+. The buyer walks immediately.

2. Ignoring the "Manager Tax"

Mistake: Selling to a strategic buyer but failing to account for the $150k GM salary required to replace the owner.Result: The buyer's due diligence uncovers the "missing" expense, and they re-trade the deal at the 11th hour, slashing the price.

3. Inconsistent Add-Backs

Mistake: Adding back "personal" expenses that are actually operational (e.g., the owner's truck that is also the delivery vehicle).Result: Credibility loss. Once a buyer finds one fake add-back, they question all of them.